AmphibiansReptiles

© 2002-2016 |

Northern Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus)

Description

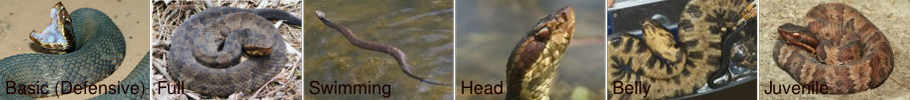

The head of a Cottonmouth is "boxy"; rather than the more roundish shape of a nonvenomous watersnake head. The cheek is tannish to whitish, usually with a dominant white stripe running from just under the eye to the corner of the mouth. The eyes are shielded from the top by scales, so that the eyes cannot be seen from directly above the snake (the eyes of nonvenomous watersnakes are visible from above). As with the young of Copperheads and Pygmy Rattlesnakes, Cottonmouth young also have brightly-tipped tails of neon yellow or green. This species is known by several other common names, including Gaper, Lowland Moccasin, Trapjaw, and Water Moccasin. (Some locals in Arkansas will call any snake seen in the water a water moccasin regardless of the species.)  HabitatsAlthough denning sites may be some distance from water, this snake is almost exclusively encountered in or around bodies of water. The source of water may be anything from a clear mountain stream to a large lake. Water sources that are slower moving, do not dry up during the summer, and have banks that are thick and lush with vegetation seem to have higher populations of Cottonmouth. My personal experience is that Cottonmouth are very rarely found at cattle ponds (although these ponds do often have high numbers of nonvenomous watersnakes). Habits and Life HistoryCottonmouth often den quite a distance from water, and may actually spend a couple of weeks near their den site basking before moving to a water source. The typical day for a Cottonmouth begins with a long basking period, that may last the entire day. Favorite basking sites are on logs, tree snags, or in the vegetation along the bank of a water source. If the day is not suitable for basking, a Cottonmouth will usually "hole up" under a rock, in thick brush, or even tucked up under the root system along the water's edge. After a long period of warming up during the day, a Cottonmouth may spend most of the night actively hunting for food, even in relatively chilly water. Cottonmouth activity heightens as the days of summer warm and the water temperatures rise. This time of year also coincides with mating season. While there are accounts of "Cottonmouth mating balls" that contain hundreds of snakes, this phenomenon has not been confirmed by science. In fact, there is a high degree of skepticism regarding these "mating balls". Most scientists have attributed these records to misinterpretation, claiming that what was really observed was simply a mass of watersnakes in a last-standing pool of a dried up creek preying upon the last surviving fish. A female who is Prey and Hunting TechniquesCottonmouth are true "garbage disposals". They may be the only species in Arkansas that might best be classified as a Adult Cottonmouth hunt primarily by patrolling the water's edge for Young Cottonmouth, with their brightly-colored tails may use caudal luring to attract small lizards and frogs to within striking range. Temperament and DefenseI have found the reputation of the Cottonmouth to far exceed its "pugnacious and mean-spirited" disposition. As someone who has spent a good deal of time working with Cottonmouth, I can honestly say that I've never felt that one of these snakes was "out to get me." Under the right conditions, a hormonal male during the breeding season may act to defend his turf, but other than this, the vast majority of actions a Cottonmouth might choose to take when approached by a human must clearly be interpreted as defensive. Cottonmouth are more territorial than most of the other snakes found in Arkansas. Being territorial, they "mark their territory", especially when approached. The musk emitted by a Cottonmouth is rather distinctive, and difficult to describe (perhaps a bit like the combined smells of a sweaty gym shirt, cat feces, and cheese?). When searching for Cottonmouth, it is not uncommon to smell one before it is seen. Along with being territorial, Cottonmouth are also more likely to hold their ground than are nonvenomous watersnakes with which they share their habitat. In some cases, I would even say that Cottonmouth watch with some amount of curiosity and leeriness when humans pillage through their territory. Once threatened, a Cottonmouth may gape open its mouth to present a cottony-white warning. This is a warning that needs to be heeded because Cottonmouth will not hesitate to strike. There is a common old wive's tale about Cottonmouth not being about to bite underwater. This is completely untrue. They can, in fact, bite underwater, on top of the water, and out of the water. I believe the vast majority of stories about a Cottonmouth "going after" someone are the result of misinterpretation and/or misidentification (of a nonvenomous watersnake). When someone walks between a Cottonmouth and the water, the Cottonmouth is likely to head in the direction of the person, but only because this is in the same direction as the water. Water provides relative safety to a snake and therefore offers a means of escape, not attack! Stories of Cottonmouth attempting to climb into boats likely hold some validity, but I strongly question these stories when the Cottonmouth "tried to climb into my boat and attack me!" I find it difficult to believe a Cottonmouth would treat a boat any different than it might a floating log; a place to "grip onto" and climb out of the water. ConservationThis species currently has no special protections in Arkansas. Much of the fear and dread that humans have of Cottonmouth comes from a misunderstanding of these snakes. This kind of snake is oftentimes killed on sight, with little to no forethought or concern. More often than not, however, the snake in question ends up being a misidentified nonvenomous watersnake. Because their preferred habitat is thickly overgrown banks along bodies of water and because they occur in relatively large numbers, the killing of one or two Cottonmouth is especially pointless, as this provides little if any added safety to humans. For one, a snake that is already seen and given space isn't going to hurt anybody. Two, if an accidental bite is going to occur, it is going to be from one of those other hundred or so Cottonmouth that live in the same area and wasn't seen. And three, attempting to kill any snake puts humans in close proximity to a snake that is now extremely agitated, defensive, and willing to bite! State Distribution and Abundance

Gallery

Contributors

Bibliography

Discussion< Eastern Copperhead | Snake | Western Diamond-backed Rattlesnake > |